Never Give Up

Digby's story

Digby is living with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a rare and progressive condition that steadily weakens children’s muscles. While treatments can help slow its impact, boys often lose the ability to walk by early adolescence and this fatal disease still has no cure.

The feeling that our son is on ‘borrowed time’ is heartbreaking”

Eva's story

Eva has progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 3 (PFIC3), a very rare inherited liver disease that over time causes severe damage. Treatment options are currently extremely limited, with affected children eventually needing a liver transplant.

Emmy’s story

Emmy has Vici syndrome, one of the most severe multi-system conditions that can affect children. Sadly, there is currently no cure or effective treatment for this devastating rare disease – and most affected children do not live beyond the age of five.

Evan’s story

Evan was diagnosed with a rare brain cancer called medulloblastoma when he was 15 months old. Luckily, he now has the all-clear but is living with complex complications as a result of the tumour and treatment effects.

Finley’s story

Finley has Diamond-Blackfan anaemia, a very rare condition where the bone marrow fails to produce enough red blood cells. There is currently no cure, so children like Finley rely on long-term treatment.

Rare disease story gallery

Paddy's story

Paddy's story

,

,  ,

,

When Paddy was born, it felt like a dream come true. He was a beautiful baby – feeding well, sleeping soundly and rarely crying. I noticed some shaking while he lay in his Moses basket, but it was dismissed as normal, just him adjusting to life outside the womb. Those early days seemed so full of promise.

But everything changed when Paddy was two weeks old. He began to scream for hours on end, inconsolable no matter what we tried. It was a cry that pierced through me, and deep down, I began to feel that something was terribly wrong. His eyes would roll and as the weeks went on, I noticed he wasn’t smiling. At eight weeks, after witnessing a clear seizure, I took him to the hospital and told them I wasn’t leaving until we had answers.

The weeks that followed were a whirlwind of tests and medications, none of which seemed to work. We were told it could take months to get genetic results and when the diagnosis finally came, it was devastating. Paddy has KCNT1-related epilepsy which is a rare, severe neurological condition with no cure. In an instant, our future as a family was transformed.

Paddy’s seizures were relentless. At his worst, he was having up to 50 a day. Watching your child go through that is something no parent should ever have to endure. Each seizure feels like a fresh wound, but we’re always there to hold his hand and comfort him through it.

Now, at five years old, Paddy is still at the developmental stage of a young baby. He hasn’t reached any milestones, and we’ve come to terms with the fact that he never will. He makes little sounds and cries to let us know if he’s unhappy or hungry, but his only real form of communication is through crying. Despite this, Paddy has a presence that fills any room. He brings so much joy and is absolutely adored by everyone who meets him. He loves being cuddled and will let us know if he’s not ready to be put down – cuddles are his favourite thing in the world.

Our goal is simple: to keep Paddy out of the hospital and to make his life as happy, healthy and comfortable as possible. Every day is about managing his condition, finding the right balance of medications and hoping they don’t stop working. It’s a delicate, exhausting process but we do it because Paddy is our world.

Paddy has faced thousands of seizures in his short life and every one of them has been heart-wrenching to witness. But he’s still here and he’s still our beautiful boy. We’re determined to make his life the best it can be, filled with love and comfort. Medical research gives us hope, not just for Paddy, but for all the children and families affected by this condition. To families like ours, hope is everything.

Henry's story

Henry's story

,

,  ,

,

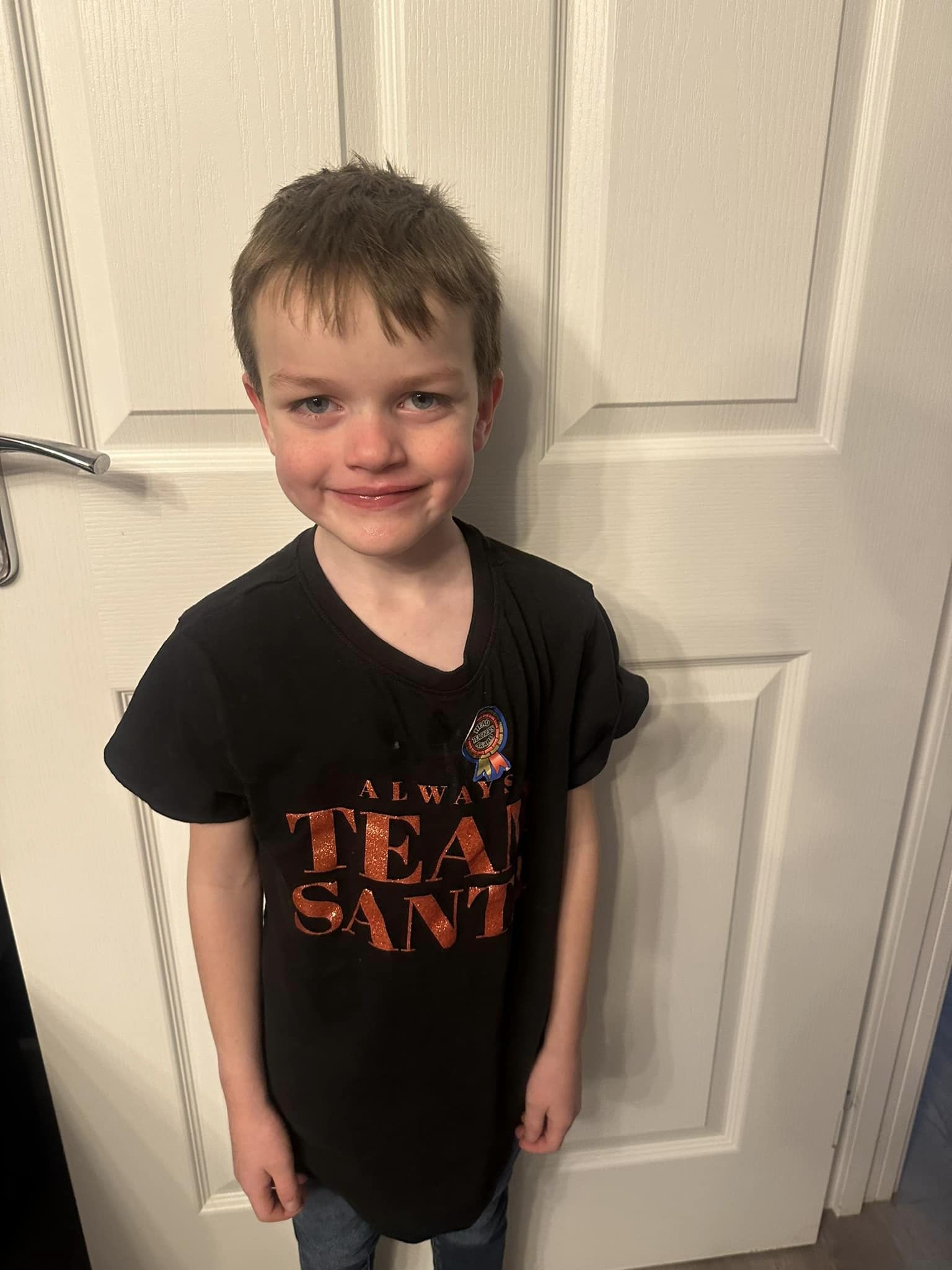

Henry is a happy, energetic boy who loves running around and playing football with friends. When you look at him you wouldn’t know that he’s harbouring a serious heart condition.

When he was just two days old, we received the shocking news that he had hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) – an inherited condition that causes a thickening of the heart muscle. Although it is rare, HCM can cause sudden death. The condition means he has stiffened heart muscle which can’t function as well as it normally would.

Henry was born via emergency caesarean at 37 weeks as doctors detected supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) – a condition which can cause the heart to suddenly beat much faster. Two days later a cardiac consultant delivered the news that as well as SVT, Henry had hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Living with both conditions is extremely dangerous and involves regular tests and monitoring. For the first two years of his life, Henry was being given three different types of medication, eight times a day.

When he was three months old, Henry was referred to Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health (GOSH) and had regular visits to monitor his heart every four weeks. We were in a constant state of worry – as we didn’t know what we were dealing with. We were told at our local hospital that Henry may have needed a heart transplant – it's a parent’s worst nightmare.

Nine times out of 10 hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is hereditary, but we haven't got it in our family so Henry’s situation is very rare. In reality we know we are incredibly lucky that the doctors detected Henry’s HCM as it could have been picked up at a catastrophic time later in life – and this way it can be monitored closely.

I used to feel very nervous when Henry would run around. I had nightmares about Henry taking part in his first sports day at school as we simply don’t know how far he is able to push himself. It feels awful to think we’re holding him back, but the thought of something happening to Henry is worse that missing out on some activities at school. Henry is very understanding and takes everything in his stride.

The family have adapted incredibly well and although we don’t want Henry to feel different, we’ve had to make sure that he is cautious. He is aware of his condition and if he feels that something isn’t quite right he knows that it’s important to take rest and let someone else know.

I don’t think we’ll ever get out of the habit of checking for defibrillators wherever we go. You hope you’ll never need to use one, but reassurance is everything when you’re living with a serious condition like HCM.

Understanding of HCM is improving but during Henry’s early days we had no idea what was going on. Being at the forefront of this research brings hope to other families and we hope that as Henry grows up his path will become steadier and easier.

Evan's story

Evan's story

,

,  ,

,

When my son Evan was 15 months old I started to notice that he was having issues with his balance, he had been pulling himself up comfortably, but he stopped doing that – he wasn’t able to hold himself up and needed help.

We spoke with doctors about our concerns and Evan was referred to a paediatrician. After being assessed at the local hospital I hadn’t even left the hospital car park when I received a call from the paediatrician telling me to take Evan straight to the Royal Victoria Infirmary in Newcastle for a scan. I later received the terrifying news that Evan had a large growth in his brain. Evan had a rare type of childhood brain cancer called medulloblastoma. It is often aggressive and difficult to treat as it is highly resistant to chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

We were told to go home and get everything they need because we were going to be in hospital for a while whilst Evan underwent brain surgery to remove the tumour.

The pandemic was a worrying and scary time. Whist we were in a way grateful to have the time at home just myself, Scott and Evan – we were also aware that due to his treatment Evan had no immune system and it was worrying in the early months when there was still a lot of unknowns about the impacts of COVID.

Ten months after finishing his treatment, Evan relapsed and we had to go through the rollercoaster of scans and treatment again which had a gruelling effect on him. He received a different kind of treatment called proton beam therapy – a type of radiotherapy treatment – on his head and spine. Evan was the second child to receive this treatment in the UK at the new Manchester Hospital. This time around, the treatment wasn’t as intense as the tumour was the size of a pea, not a golf ball.

Four years on from finishing his treatment Evan is doing really well. We take him for annual scans and thankfully he is tumour free. Generally Evan is a very happy little boy – he loves books, playing with his toys, swimming, going out for walks and feeding the ducks.

Due to Evan’s age when he became unwell, he has a lot of complex complications and delays with his development. He has hearing loss, issues with mobility and learning. We were told by the doctors that the older Evan gets, the wider the development gap will get between him and his peers.

Evan goes to a special school where he gets additional help and attends smaller classes where the education is tailored to his needs. He needs to be given a daily growth hormone due to the treatment he received and his pituitary gland being affected by radiotherapy.

He sees various specialists such as a physiotherapist, speech and language therapist, occupational therapist and sensory support due to a condition which affects his sight. He has high frequency hearing loss due to the chemotherapy and is supposed to wear hearing aids but sometimes at this age he can be a little resistant and takes them out.

We are aware that much of the treatment and drugs Evan received were for adults and not designed for small children. If a kinder type of treatment had been around six years ago we’ll never know if Evan’s outlook may have been different.

Understanding of medulloblastoma in children has come a long way, even during Evan’s short life. Chemotherapy is such an intense treatment, for families any chance for a better quality of life during and after treatment would be re-assuring. Learning about research developments is bittersweet as we know it won’t be in time for our boy, but it is promising for any other family facing what we faced.

Emmy's story

Emmy's story

,

,  ,

,

Despite an easy pregnancy and delivery, from Emmy’s first day in the postnatal ward, I felt there was something wrong.

She found it incredibly difficult to feed and as the weeks progressed with Emmy missing key milestones, my husband and my fears grew.

I spoke to every health professional you have at that first line, but we were just told you’ve got to wait until 12 weeks. When Emmy did finally reach 12 weeks, she developed bronchiolitis, and happened to be admitted to the hospital by the lead paediatrician.

I seized the chance to list all the things that were terrifying me. I explained that I didn’t think Emmy could see, that we thought she had global developmental delay, that she wasn’t smiling or interacting, wasn’t responding to her name, couldn’t grasp…

Thankfully, our concerns were heard, and Emmy was sent for an MRI scan – and it all snowballed from there.

The scan showed significant structural changes in Emmy’s brain that confirmed that our baby girl couldn’t see and that she would have issues with the movement and muscle tone on one side of her body.

But it was when Emmy was 18 months old that we received the most heartbreaking news…Emmy had Vici syndrome.

We were completely blindsided. In the months before she seemed better. We had a good grasp of her care, and she seemed to be thriving again. We really didn’t think there could be anything more so catastrophically wrong. So, to learn about Vici syndrome. That there was no cure. It was horrific.

Our beautiful girl is now two years old and is blind, unable to walk or talk and is tube fed. Emmy also suffers from epilepsy.

Her condition is so rare and complex we quickly round ourselves under multiple medical teams. There was a brain person, an eye person, a hormone person, a dietician…

Life has been totally different and incredibly hard, but in some ways, it’s exactly the same as anyone else caring for their child, you find rhythms and ways to make each other happy and that’s what we do.

Sometimes I’m asked whether or not I think Emmy knows who I am. It is an extraordinary thing to ask a mum. So close to the bone. The truth is, I can’t be 100% sure.

But I do know that Emmy is comforted when she’s with me. She loves a snuggle and she is very communicative once you learn her cues and has a close bond with her big sister, Tilly.

Thinking about the future…it’s daunting. I hope for the same things that all parents hope for – health, happiness and longevity but within a different framework, I guess.

I hope we’ll have longer with Emmy than those worst-case predictions, but more than that, I hope that we have a lot of quality time. I hope that Emmy is not in hospital, that she is well and alert and expressing enjoyment at the things we do with her and her surroundings. And I hope that one day there is a cure.

Finley's fight - DBA

Finley's fight - DBA

,

,  ,

,

We didn’t realise when we named him, but Finley means warrior, and that he truly is. He has amazed us with all he has overcome in early years of life. In just his first 24 hours of life, Finley had already undergone three blood transfusions after tests found he was severely anaemic.

Shortly after, he was found to have a serious heart condition, and a scan showed enlarged ventricles in his brain that would go on to affect his development. Then at six-weeks-old, Finley was diagnosed with profound hearing loss.

We found ourselves on a conveyor belt of poor prognosis and just surviving each day.

It wasn’t until Finley was three months that he was finally diagnosed with Diamond-Blackfan anaemia (DBA), and doctors confirmed that both his heart condition and hearing loss were linked to this rare condition.

It was heartbreaking knowing there was no cure, and the challenges Finley would face. At just 13 months old, Finley endured an eight-hour operation to fit cochlear implants to improve his hearing. This was followed by open-heart surgery when he reached three.

Our little boy is now six years old and has monthly blood tests, followed by a four-hour blood transfusion the next day to combat his severe anaemia. It’s always a worrying time, as the tranfusions can cause a build-up of iron in the body that Finley’s bone marrow can’t process in the usual way. If left untreated, it can cause organ failure, so we have to ensure Finley takes daily tablets to remove excess iron, but these too come with side effects.

His care is a delicate balance that requires constant monitoring. This includes regular bone marrow and liver biopsies – which are always so nerve-wracking – as DBA increases his chances of developing cancer.

In the future, Finley may also need a bone marrow transplant if the transfusions stop working. It's not the path we thought we would be on as a family, but we always try to remain positive.

Finley never complains or lets his challenges define him, but we dream of a cure.

George's story

George's story

,

,  ,

,

George entered the world after a long-induced labour, due to reduced movements at 37 weeks and 5 days. We were smitten with our gorgeous boy, who seemed perfectly healthy until a few hours after his birth, George began gasping for air and turned blue. He was rushed off to the neonatal intensive care unit and placed on a ventilator. It was just awful watching his oxygen levels constantly rise and fall and being powerless to do anything.

Tests revealed George had lung surfactant deficiency, a rare condition caused by a fault in the ABCA3 gene that causes serious breathing difficulties.

I’ll never forget the moment doctors told us his condition wasn’t ‘compatible with life’. That there was no cure and few treatments. I broke down sobbing. I just couldn’t understand how a condition I had never even heard of, could take my little boy’s life.

The next few weeks, my husband and I were in a state of limbo waiting, hoping, that George would pull through. That I could tell his big sister, Holly, that everything was going to be OK. But we were warned to prepare for the worst, so we had George christened at his bedside and planned things no parent should ever have to think about.

After weeks of heartbreaking uncertainty, our gorgeous George became our little miracle. He defied the odds and was finally well enough to go home. I don’t think I can put into words the relief I felt.

But George wasn’t cured and caring for a child with a rare condition hasn’t been easy. George had to be hooked up to oxygen 24/7 and he became so scared of anything in his mouth potentially blocking his airway that he had to be tube-fed.

Whenever he caught a virus or had difficulties with his breathing or feeding, we were back in the hospital. There have been many ups and downs, but we cope and have made happy memories together.

And now our little boy is seven years old and smashing life! He is full of energy, life and naughtiness. I’m so proud of him. He no longer needs oxygen support and recently he got his feeding tube removed – it’s the first time he’s been tube-free since birth! I sobbed for hours. It was a huge moment for the whole family.

I feel so fortunate that George is here and doing well because I know the odds were against us. It’s the work of organisations like Action that takes us a step closer to that day. But their work is only possible thanks to the kindness of people like you.

George’s older sister Holly copes remarkably well. We rely on her for help sometimes, but she is always smiling. Life is challenging but we cope. We have no choice but to get on with it.

Please be aware that the stories and photos in this gallery are personal stories written by people who have shared them with Action Medical Research and reflect their own personal experiences of children’s rare diseases.