breadcrumb navigation:

- Home /

- Research /

- Family stories /

-

current page

James and Samuel: X-linked lymphoproliferative disease (XLP)

James and Samuel: X-linked lymphoproliferative disease (XLP)

Published on

Updated:

James and Samuel's story

X-linked lymphoproliferative disease (XLP)

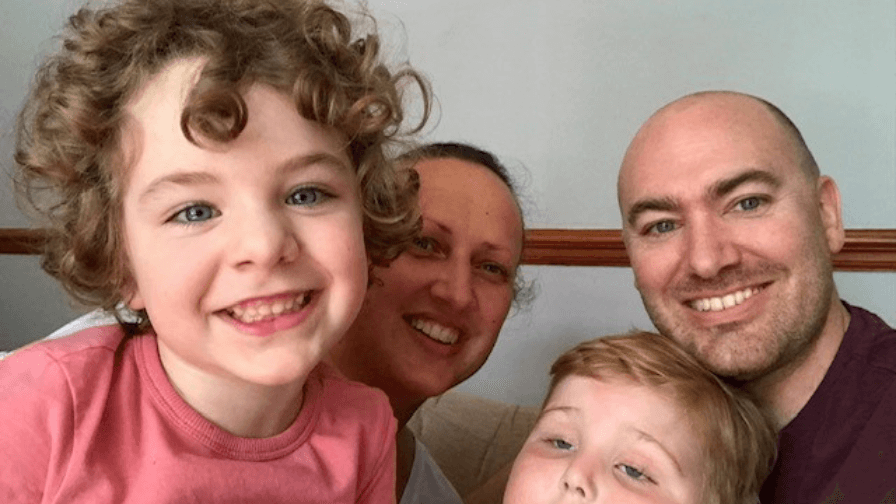

Rachel and Paul’s eldest son, James, was a lively, articulate boy who loved to sing, run, and climb. However, a few months after he turned three, he fell seriously ill. “He had a chest infection, was extremely lethargic and slept constantly. He stopped talking and would just babble like a baby,” Rachel recalls. After undergoing a battery of tests, James was diagnosed with encephalitis – a rare but serious type of brain inflammation.

The family agreed to undergo genetic testing to determine the cause of James’ condition. The results revealed that he had X-linked lymphoproliferative disease type 1 (XLP1).

XLP is a rare genetic disorder that affects boys. Without treatment, around seven in every 10 boys with XLP will not survive beyond the age of 10. Medicines benefit boys with XLP and bone marrow transplants can cure the condition, but this means finding a donor who is a good match. For transplants to work well, it’s best to carry them out early in the disease process and sadly, if transplants come too late or donors cannot be found, boys with XLP remain at risk of losing their lives.

Following James’ diagnosis, his parents Rachel and Paul were told to test all their children. They arranged for their younger son Samuel, who was 20 months old at the time, to be tested. They received the devastating news that Samuel also had XLP.

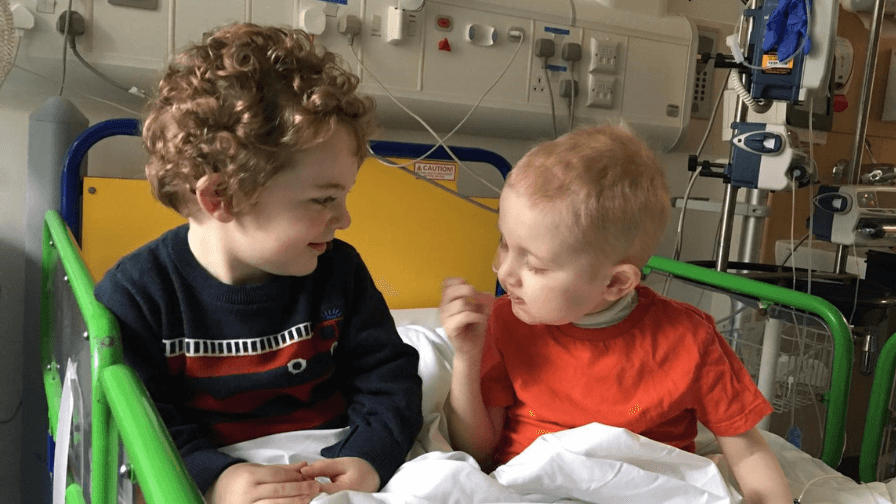

In July 2018, James was admitted to Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) for a bone marrow transplant. Samuel joined him in early December 2018. “It was an incredibly worrying time for us all,” Rachel recalls. “James was very unwell going into his operation and experienced difficult side effects.”

Although the transplant helped James fight the disease, he had already sustained severe brain damage from encephalitis. He developed profound learning disabilities, mobility challenges and required 24/7 care. Sadly, James passed away in August 2023. His loss has left an immeasurable void in his family’s lives. “James was a joy. He fought so hard and we cherished every moment with him. He was a miracle. The odds were against him, and he really shouldn’t have made it as long as he did,” Rachel said. “It’s only due to the brilliance of medical research that we got to have him with us for as long as we did.”

Samuel, now thriving, has a promising future ahead. However, Rachel knows that XLP remains a significant concern for families like theirs. With the help of funding from Action Medical Research, Dr Claire Booth at the UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health has been working on a groundbreaking gene-editing therapy. This innovative approach aims to correct the faulty gene in a child’s blood stem cells, offering a potential cure that could prevent boys with XLP from having to endure transplants.

Having seen both of her sons undergo bone marrow transplants, Rachel believes this new treatment could change lives. “If Samuel grows up and has a daughter, XLP could still be passed on. The possibility of a safer, more effective treatment for future generations is incredible,” she says.

Reflecting on their journey as a family, Rachel adds: “Anything that stops a child from having to go through a transplant is a no-brainer.”

TOGETHER WE CAN FIGHT XLP

Support our latest appeal and 100% of your donation will fund groundbreaking research that offers hope of curing XLP